Translate this page into:

Knowledge about chest imaging findings in COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo

*Corresponding author: Olivier Mukuku, Department of Maternal and Child Health, High Institute of Medical Techniques of Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. oliviermukuku@yahoo.fr

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ndabahweje DN, Kahindo CK, Mukuku O, Wembonyama SO, Tsongo ZK. Knowledge about chest imaging findings in COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Pan Afr Thorac Soc. 2024;5:5-10. doi: 10.25259/JPATS_17_2023

Abstract

Objectives:

Chest imaging, particularly computed tomography, plays a crucial role in the evaluation of patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. This study aimed to assess physicians’ knowledge about chest imaging findings in COVID-19 patients in Goma, North Kivu Province (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Materials and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study involving 202 physicians who responded to the survey questionnaire. Performance was tested in terms of the mean score and proportions of correct answers for each questionnaire item. Multiple logistic regressions were used to identify factors associated with good knowledge.

Results:

The mean score obtained by respondents was 8.55 ± 2.49 out of 16 points. The proportion of physicians with more than 60% correct answers was 37.13%. There was no significant statistical association between good knowledge and the demographic and professional characteristics of the respondents (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

This study found that physicians’ knowledge about chest imaging findings in COVID-19 patients is poor. This lack of sufficient information on the part of healthcare workers indicates the need to develop continuing education programs.

Keywords

Coronavirus disease 2019

Chest imaging

Knowledge

Physicians

Healthcare worker

Goma

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is the infectious agent behind coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).[1] In December 2019, authorities in Wuhan, China, reported the first human cases of COVID-19.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO), meanwhile, declared the pandemic on March 12, 2020, following the rapid spread of the disease worldwide.[3] As of July 12, 2023, there have been more than 6.5 million verified deaths attributable to COVID-19 and approximately 768 million confirmed cases.[4]

In the majority of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, chest imaging findings included bilateral lung involvement and ground-glass opacities (first published in January 2020).[5] Since then, numerous studies on COVID-19 chest computed tomography (CT) imaging have been rapidly published. The appropriate use of chest CT in COVID-19 patients should be determined by experience and, more importantly, by the growing body of scientific evidence that has come to light since the emergence of the disease.[6,7] Chest imaging, including radiography and CT, plays a crucial role in the evaluation of COVID-19 patients.

Healthcare workers (HCWs), particularly physicians and nurses, need to be well-informed about the appropriate use of these imaging techniques to diagnose, assess the severity, and monitor the progression of disease in COVID-19 patients.[8] HCWs must be able to determine the appropriate indications for chest imaging in COVID-19 patients. This includes assessment of clinical symptoms, such as fever, cough, and dyspnea, as well as identification of risk factors and potential complications. A thorough knowledge of current guidelines and protocols is essential to avoid inappropriate use of chest imaging and to optimize available resources. The ability to understand and correctly interpret the results of chest imaging is crucial for HCWs.[9,10] This includes recognition of chest imaging findings of COVID-19 infection, such as bilateral and peripheral ground-glass opacities, as well as the different presentations of the disease, ranging from mild-to-severe forms. Accurate assessment of the severity of COVID-19 infection based on chest imaging findings enables appropriate treatment and monitoring decisions to be made.[11,12]

Assessing HCW’s knowledge about chest imaging findings of COVID-19 infection is of paramount importance in ensuring quality care and effective management of COVID-19 patients. In the city of Goma, as in most other towns in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), there is a serious shortage of radiology specialists. In most cases, general practitioners and other specialists are called on to interpret radiological images themselves. The present study was carried out in one of the provinces of the DRC which has seen a large number of cases of COVID-19. We would point out that, although the WHO has declared the pandemic over, this does not mean that there are no more cases of COVID-19, as we continue to observe severe cases of COVID-19 in hospitals. Hence, the interest in conducting this study, which aims to assess the level of knowledge of physicians regarding chest imaging of COVID-19 patients in Goma City, North Kivu Province (in the DRC), to identify continuing education needs and training improvement strategies to optimize medical imaging skills in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted in Goma city, located in the South of North Kivu Province in the DRC. Goma City is the provincial capital, with an estimated population of approximately 2 million. It is the focal point in terms of health services for the entire province and surrounding areas.

For the present study, all physicians (general practitioners and specialists) from different health facilities in the city were deemed eligible and were randomly selected. The exclusion criterion was if an HCW was on vacation or absent from work on the day of data collection or if he/she worked in a health facility not selected for the study. The study covered health centers (HCs), general referral hospitals (GRHs), and private clinics (PCs). Data were collected from June 1 to June 30, 2023.

Recruited surveyors received intensive training, covering the context of the current survey, a detailed interpretation of the survey instrument, and a mock survey test. Finally, a total of 5 investigators were recruited. They explained the purpose and procedure of the study and obtained written informed consent from each respondent before asking them to complete the questionnaire. On average, the survey lasted 10–15 min.

To collect the data, we used a questionnaire developed and pre-tested in a pilot study involving ten physicians from three health facilities. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire and provide feedback on the relevance, clarity, and difficulty of the questionnaire items. This led to the adaptation, revision, addition, or deletion of certain elements of the survey tool.

This questionnaire contains a series of 16 main questions relating to knowledge of chest X-ray indications in COVID-19, indications of chest CT in COVID-19, and chest CT images suggestive of COVID-19.

The questionnaire was closed and self-administered with three assertions (“Yes,” “No,” and “Don’t know”) for each question, of which only one was considered correct. Respondents were given the option of choosing “Do not know” to discourage guesswork. To calculate the respondent’s total score, 1 point was awarded for each item answered correctly and 0 points were awarded for incorrect answers. Scores ranged from 0 to 16 and were subdivided into two groups: A score <10 represented a poor level of knowledge and a score ≥10 signified a good level of knowledge.

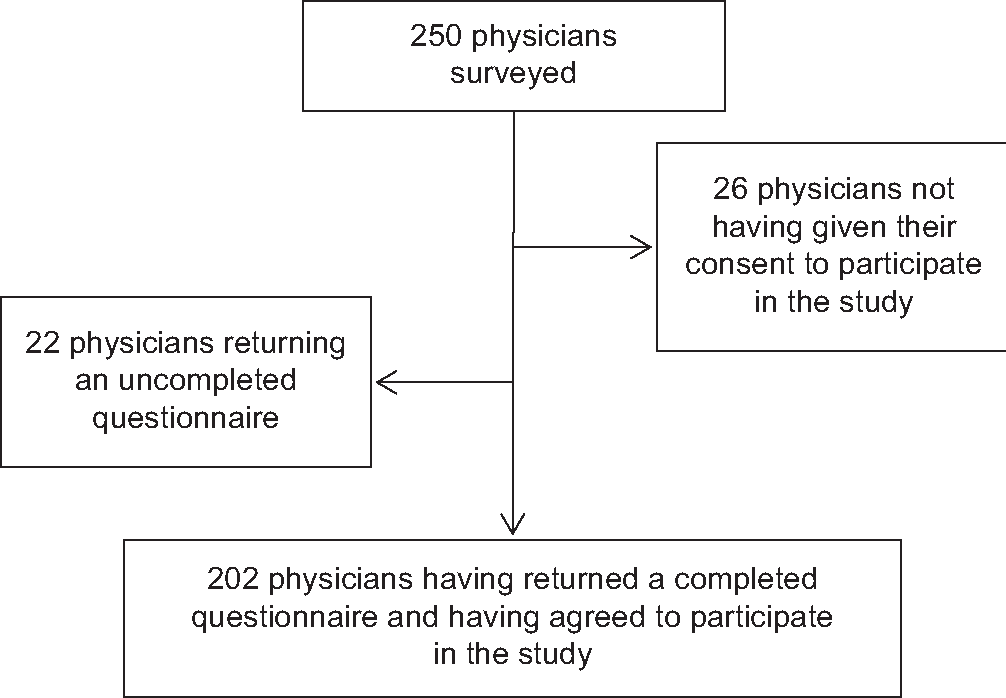

A total of 250 questionnaires were distributed, and 224 were returned. Of the returned questionnaires, 202 were fully completed and were included for further analysis [Figure 1]. This represented an effective response rate of 90.17%.

- Participant recruitment.

To characterize the study participants, the following variables were used: Age, gender, medical title, type of health facility where they worked, years of clinical practice, and training in relation to COVID-19. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (version 16). Data analysis included descriptive statistics, frequencies, means, and Chi-square calculations to determine significance. Demographic (age and gender) and professional variables (medical title, type of health training, professional experience, and whether or not they had attended a COVID-19 education session in the past 2 years) were analyzed to determine whether participants had significantly different knowledge scores. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Goma (approval no. UNIGOM/CEM/009/2023). Informed consent was obtained from all participants after the study was initiated. Confidentiality was ensured, and participants were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without prior explanation on their part.

RESULTS

The 202 respondents had a mean age of 39.55 ± 7.96 years, and most (81.19%) were men. Three out of four respondents were general practitioners. Over 43% of respondents worked on PCs. On average, respondents had 9.69 years of clinical experience, and only approximately 70% had received training on COVID-19 in the 2 years preceding the survey [Table 1].

| Variable | Number (n=202) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±standard deviation | 39.55±7.96 | |

| 26–30 | 24 | 11.88 |

| 31–35 | 42 | 20.79 |

| 36–40 | 53 | 26.24 |

| >40 | 83 | 41.09 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 164 | 81.19 |

| Female | 38 | 18.81 |

| Medical title | ||

| General practitioner | 153 | 75.74 |

| Specialist | 49 | 24.26 |

| Type of health facility | ||

| Private clinic | 88 | 43.56 |

| General reference hospital | 84 | 41.58 |

| Health center | 30 | 14.85 |

| Years of clinical practice, mean±standard deviation |

9.69±6.48 | |

| <5 | 47 | 23.27 |

| 5–10 | 78 | 38.61 |

| >10 | 77 | 38.12 |

| Training or attending a conference on the management of COVID-19 infection within the past 2 years |

||

| Yes | 140 | 69.31 |

| No | 62 | 30.69 |

| Have a family member who has suffered from COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 184 | 91.09 |

| No | 18 | 8.91 |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019

Of the 202 respondents, only 75 (37.13%; 95% confidence interval: 30.45–44.19%) had good knowledge (knowledge score ≥10), and a further 127 (62.87%; 95% confidence interval: 55.81–69.55%) had poor knowledge (knowledge score <10). The mean score obtained by respondents was 8.55 ± 2.49 out of a total of 16 points. The mean knowledge scores were not significantly different between the different health facilities [Table 2]. We noted statistically higher proportions of correct answers among respondents in PCs than among respondents practicing in GRHs and HCs concerning three items: “Conventional chest X-ray does, however, give an idea of the approximate extent of lung involvement,” “In the event of clinical suspicion of COVID-19 and a negative polymerase chain reaction test, a chest CT can be performed,” and “The existence of intralobular reticulations with a crazy-paving appearance is suggestive of COVID-19.” There were no statistically significant differences between HCWs from different facilities in the other knowledge assessment items on chest imaging for COVID-19 (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

| Items | Number (Percentage) of respondents who answered correctly | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=202) | Health center (n=30) | General Reference Hospital (n=84) | Private clinic (n=88) | ||

| Conventional chest X-ray images suggestive of COVID-19 are opacification, often in the periphery and the lower lungs | 134 (66.34%) | 23 (76.67%) | 51 (60.71%) | 60 (68.18%) | 0.252 |

| Chest X-ray is recommended for routine diagnosis of COVID-19 | 88 (43.56%) | 17 (56.67%) | 41 (48.81%) | 30 (34.09%) | 0.044 |

| Chest X-rays can be useful for monitoring patients with COVID-19 | 171 (84.86%) | 28 (93.33%) | 68 (80.95%) | 75 (85.23%) | 0.266 |

| Conventional chest X-ray is not indicated for mild or early COVID-19 infections | 81 (40.10%) | 10 (33.33%) | 34 (40.48%) | 37 (42.05%) | 0.699 |

| Conventional chest X-rays give an idea of the approximate extent of lung involvement | 15 (7.43%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (4.76%) | 11 (12.50%) | 0.037 |

| Chest CT should not be performed routinely in the absence of signs of poor respiratory tolerance | 127 (62.87%) | 22 (73.33%) | 48 (57.14%) | 57 (64.77%) | 0.256 |

| Chest CT performs very well in the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 (bacterial pneumonia, infectious bronchiolitis, cardiogenic pulmonary edema) | 161 (79.70%) | 25 (83.33%) | 63 (75.00%) | 73 (82.95%) | 0.374 |

| Chest CT is recommended for routine diagnosis of COVID-19 | 137 (67.82%) | 24 (80.00%) | 50 (59.52%) | 63 (71.59%) | 0.072 |

| Chest CT is recommended for patients with suspected COVID-19 infection requiring hospitalization (regardless of PCR result) | 117 (57.92%) | 13 (43.33%) | 46 (54.76%) | 58 (65.91%) | 0.072 |

| Chest CT to assess the severity of COVID-19 | 170 (84.16%) | 26 (86.67%) | 67 (79.76%) | 77 (87.50%) | 0.350 |

| In the event of clinical suspicion of COVID-19 and a negative PCR test, a chest CT may be performed | 129 (63.86%) | 15 (50.00%) | 50 (59.52%) | 64 (72.73%) | 0.046 |

| Ground-glass opacities (areas of increased lung parenchyma density without obliterating the pulmonary vessels) are suggestive of COVID-19 | 122 (60.40%) | 14 (46.67%) | 49 (58.33%) | 59 (67.05%) | 0.126 |

| Unsystematized consolidation (non-systematic increase in lung density obliterating the pulmonary vessels) is suggestive of COVID-19 | 82 (40.59%) | 13 (43.33%) | 33 (39.29%) | 36 (40.91%) | 0.925 |

| Intralobular reticulations with a crazy paving appearance are suggestive of COVID-19 | 73 (36.14%) | 9 (30.00%) | 22 (26.19%) | 42 (47.73%) | 0.010 |

| Bronchogenic miliaria is suggestive of COVID-19 | 59 (29.21%) | 10 (33.33%) | 28 (33.33%) | 21 (23.86%) | 0.341 |

| Hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes with a hypodense center are suggestive of COVID-19 | 62 (30.69%) | 7 (23.33%) | 27 (32.14%) | 28 (31.82%) | 0.638 |

| Mean total score (standard deviation) | 8.55 (2.49) | 8.53 (1.99) | 8.11 (2.72) | 9.00 (2.36) | 0.067 |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, CT: Computed tomography, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, n: Number

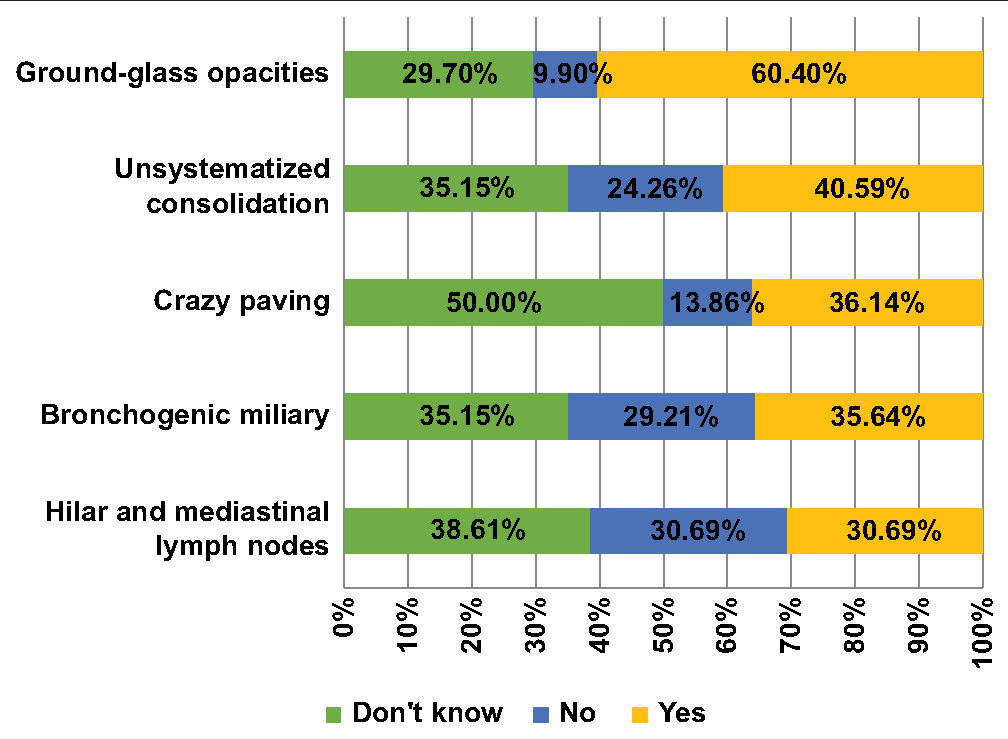

Figure 2 shows the distribution of participants’ responses to chest CT images suggestive of COVID-19 infection. Ground-glass opacities were known by 60.4% of the respondents, unsystematized consolidations by 40.59%, and crazy paving by 36.14%. Over 30% of respondents thought that bronchogenic miliary, hilar, and mediastinal lymph nodes would be CT images suggestive of COVID-19 infection.

- Physicians’ responses to chest computed tomography images suggestive of coronavirus disease 2019 infection.

After logistic regression, we found that the level of knowledge was not influenced by respondents’ demographic and professional characteristics [Table 3].

| Variable | Total | Good knowledge | Poor knowledge | Adjusted OR (95% confidence interval) | -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=202) | (n=75), n (%) | (n=127), n (%) | |||

| Age | |||||

| 26–30 years | 24 | 7 (29.17) | 17 (70.83) | 1.00 | |

| 31–35 years | 42 | 14 (33.33) | 28 (66.67) | 1.27 (0.40–3.96) | 0.686 |

| 36–40 years | 53 | 26 (49.06) | 27 (50.94) | 2.28 (0.71–7.37) | 0.168 |

| >40 years | 83 | 28 (3.73) | 55 (66.27) | 1.29 (0.33–5.11) | 0.714 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 38 | 12 (31.58) | 26 (68.42) | 1.00 | |

| Male | 164 | 63 (38.41) | 101 (61.59) | 1.22 (0.55–2.71) | 0.633 |

| Medical title | |||||

| General practitioner | 153 | 57 (37.25) | 96 (62.75) | 1.00 | |

| Specialist | 49 | 18 (36.73) | 31 (63.27) | 0.86 (0.39–1.90) | 0.714 |

| Type of health facility | |||||

| Health center | 30 | 9 (30.00) | 21 (70.00) | 1.00 | |

| General reference hospital | 84 | 23 (27.38) | 61 (72.62) | 1.03 (0.39–2.70) | 0.959 |

| Private clinic | 88 | 43 (48.86) | 45 (51.14) | 2.42 (0.94–6.25) | 0.068 |

| Years of clinical practice | |||||

| <5 years | 47 | 15 (31.91) | 32 (68.09) | 1.00 | |

| 5–10 years | 78 | 31 (39.74) | 47 (60.26) | 1.14 (0.48–2.73) | 0.768 |

| >10 years | 77 | 29 (37.66) | 48 (62.34) | 1.20 (0.38–3.77) | 0.753 |

| Training or attending a conference on the management of COVID-19 infection within the past 2 years | |||||

| Yes | 140 | 55 (39.29) | 85 (60.71) | 1.34 (0.68–2.67) | 0.400 |

| No | 62 | 20 (32.26) | 42 (67.74) | 1.00 | |

| Have a family member who has suffered from COVID-19 | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 68 (36.96) | 116 (63.04) | 0.89 (0.30–2.60) | 0.833 |

| No | 184 | 7 (38.89) | 11 (61.11) | 1.00 | |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, OR: Odds ratio, n: Number, %: Percentage

DISCUSSION

The present study assessed physicians’ knowledge about chest imaging findings in COVID-19 patients. In general, it is recognized that the level of knowledge indirectly translates into the quality of healthcare delivered to patients by HCWs. The assessment of knowledge among HCWs is of paramount importance in ensuring the quality and safety of patient care.

The study looked only at physicians who had treated COVID-19 patients and had indicated chest CT at least once in a COVID-19 patient. In the DRC in general and in Goma in particular, due to the lack of radiology specialists, general practitioners, and specialists interpret the chest imaging findings themselves. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Congolese survey to assess knowledge about chest imaging in COVID-19 among physicians. The results of the present study indicate that a small proportion of physicians surveyed had good overall knowledge (37.13%). This study highlights variations in knowledge levels and potential gaps identified among physicians.

The emergence of COVID-19 has led to a significant increase in demand for chest imaging techniques to assess the severity of pulmonary infection, monitor disease progression, and guide treatment decisions. Medical imaging methods, in particular chest CT, have become invaluable tools in the clinical management of COVID-19.[6,7] Chest CT is considered more sensitive than chest radiography for detecting lung abnormalities associated with COVID-19. Characteristic findings include ground-glass opacities, consolidations, crazy pavings, and mosaic nodules. The distribution of these abnormalities is often bilateral, predominating in the peripheral and basal regions of the lungs.[6,13] Specific radiological features may be observed in certain patient subgroups; for example, patients with more severe forms of COVID-19 may present with extensive lung involvement with a predominance of consolidations and ground-glass opacities. In addition, the presence of pulmonary thromboembolism and pleural effusions has also been reported in some patients.[11,12]

In the present study, chest CT images suggestive of COVID-19 infection recognized by respondents were ground-glass opacities (60.4%), unsystematized consolidation (40.59%), and crazy paving (36.14%). Chest CT images play an important role in the management of patients with COVID-19. They help assess the severity of infection, monitor disease progression, and guide therapeutic decisions. Radiological images can also provide information on potential complications, such as the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome or pulmonary thromboembolism. A proper understanding of radiological images enables HCWs to provide targeted and effective care for patients with COVID-19.[14]

The results of the present study underline the need for improved training and education of HCWs regarding the indications and interpretation of chest radiological images associated with COVID-19 infection. Better knowledge of the specific radiological manifestations of COVID-19 would enable more informed decision-making, better coordination of care, and an overall improvement in clinical outcomes. Further efforts should be made to develop continuing education programs, teaching resources, and standardized reference protocols to help health-care personnel strengthen their skills in chest imaging during COVID-19.

The strength of our study is the inclusion of physicians who provided health services to patients with COVID-19 in Goma City’s public and private health facilities. This study fills an important gap in the literature by documenting knowledge about the use of chest imaging for COVID-19 in Goma. However, there are some limitations. We relied on self-reporting by respondents and self-reported knowledge may have led to a bias in responses, as these can be subjective and personal. In addition, a more formative approach through focus groups or interviews would provide a better understanding of the complex nuances in the indications for chest imaging in COVID-19, in addition to the quantitative results. Attempts to generalize the results of this study must be cautious.

CONCLUSION

The present study has highlighted that in the absence of expert radiologist support in the DRC, HCWs’ knowledge about chest imaging findings in COVID-19 patients is poor. Improved knowledge through further training on chest imaging associated with COVID-19 could lead to improved management and reduced morbidity and mortality associated with this disease in settings where it remains common.

Authors’ contributions

All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The authors declare that they have taken the ethical approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Goma. The ethical approval number is UNIGOM/CEM/009/2023 approval date is June 9th, 2023.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author(s) confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Coronavirus. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 [Last accessed on 2023 July 16]

- [Google Scholar]

- Pneumonia of unknown cause. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en [Last accessed on 2023 July 16]

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. 2020. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/healthtopics/health-emergencies/coronaviruscovid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic [Last accessed on 2023 July 16]

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int [Last accessed on 2023 July 13]

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chest CT in COVID-19: What the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2020;40:1848-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Structured reporting of chest CT provides high sensitivity and specificity for early diagnosis of COVID-19 in a clinical routine setting. Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20200574.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Use of chest imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID-19: A WHO rapid advice guide. Radiology. 2021;298:E63-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chest CT score in COVID-19 patients: Correlation with disease severity and short-term prognosis. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6808-17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The usefulness of chest CT imaging in patients with suspected or diagnosed COVID-19: A review of literature. Chest. 2021;160:652-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CT manifestations of Coronavirus disease-2019: A retrospective analysis of 73 cases by disease severity. Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108941.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chest CT accuracy in diagnosing COVID-19 during the peak of the Italian epidemic: A retrospective correlation with RT-PCR testing and analysis of discordant cases. Eur J Radiol. 2020;130:109192.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Review of chest CT manifestations of COVID-19 infection. Eur J Radiol Open. 2020;7:100239.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CT characteristics of patients infected with 2019 novel Coronavirus: Association with clinical type. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:408-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]